Islam came to Arabia through envoys from Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) who arrived in the regionin AD630. Dibba, inpresent-day Fujairah, was the site of one of the major battles of the Ridda Wars (or Wars of Apostacy launched by Caliph Abu Bakr against Arabian rebels) after Prophet Mohammed’s death.The defeat of there be ls in this battle asserted the dominance of Islamin the Arabianpeninsula. Moreover, Julfar (present-dayRasAlKhaimah) was used in AD637 as as tag in gpost by the Caliphate in their conques to fthe Sasanian EmpireinIran.

This ushered in an age of the Caliphate on both sides of the Arabian Gulf – the Umayyad Caliphate (AD661–750) and the Abbasid Caliphate (AD750–1258), which succeeded in unifying the various Islamic tribes and people sin Arabia. This era is considered to be the Islamic Golden Age due to numerous cultural, social, scientific and economic achievements. This era is of particular importance in RasAlKhaimah’shistory. It during this time that Julfars treng the ned its position as one of Arabia’s most important trading hubs, mainly possible because of the unification of several Islamic empires, which led to the expansion of trade and tradenet works.

THE ADVENT OF ISLAM

Our knowledge of south-east Arabia in the years leading up to the arrival of Islam is scant, but for the first time our understanding of historical events shifts from a complete reliance on archaeology to the availability of written sources. Arab chroniclers during the Islamic Golden Age, sometimes writing from a great historical distance, provide us with a tantalising image of south-east Arabia on the eve of Islam. An image that is populated with kings and princes, empires and warfare, merchants and trade. At the heart of which often lay the ancient trading town of Julfar.

According to the ninth century historian Ahmad Ibn Yahya al-Baladhuri, author of the Kitab Futuh al-Buldan (‘Book of the Conquests of Lands’), in the years prior to Islam much of Oman and the eastern coast of the UAE was dominated by a branch of the Azd tribe known as the Banu Al Julanda. Originally from Yemen, the Azd had migrated to south-east Arabia in successive waves from the early second century onwards, joining other tribes and non-Azd groups (often referred to as ‘Nizar’ by chroniclers) who inhabited the interior and what is now the UAE. The geographer and historian Ahmad al-Ya’qubi, whose Tarikh al-Yaqubi is an account of the pre-Islamic peoples of the Arabian peninsula, mentions other branches of the Azd, including the Al-Huddan, who are believed to have resided along the northern coast of the UAE, including Ras Al Khaimah. Other tribes would have been concentrated around particular wadis, towns or villages and would have either integrated with the indigenous population or moved elsewhere.

Any Persian presence in south-east Arabia during the sixth century was largely confined to the coast, with the Sasanian king Khosrow I (AD 531–579) concluding an understanding of territorial influence with the region’s Arab tribes. That understanding stated that the tribes would control most of the interior and some locations along the coast, with the Sasanian king also recognising the tribes’ rights to supervise the markets at Dibba, Sohar and Julfar. Accordingly, the Banu Al Julanda extended their authority over large parts of the region, although other tribal powers were able to compete for influence in Dibba and along the northern coast.

According to Islamic sources, it is clear that these tribal populations occupied a number of professions, including trade, industry (such as textiles and copper), agriculture, hunting, fishing, shepherding and pearl diving. In the markets of Julfar, Dibba, Sohar and Muscat, commodities such as frankincense, spices, swords, pearls, copper, silk, food and wheat were sold, with goods transported via land and maritime routes that connected the region with the outside world. Such was south-east Arabia’s strategic location that its markets were visited by merchants from as far afield as India and Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia).

In the early seventh century, two brothers of the Al Julanda family dominated the region’s political landscape from their base at Sohar on the Batinah coast of Oman. Jayfar bin Al Julanda and Abd bin Al Julanda, described as the ‘two kings’ of Oman, are mentioned in various historical sources, including those of al-Yaqubi and Ibn Hisham, who is perhaps best known as the editor of Ibn Ishaq’s biography of the Prophet Muhammad. The Al Julandas were the sons of Al Julanda Al-Azdi and in the years leading up to the arrival of Islam were in conflict with another branch of the Azd – the Atik – whose base was at Dibba in modern-day Fujairah. Due to the continued presence of Persian forces on the eastern seaboard, the two brothers also challenged the Sasanian Empire for control of the coast. Whether Ras Al Khaimah was under Al Julanda control at this point of time is unknown, but subsequent events suggest it probably was.

It was into this political arena that Islam first entered in AD 630. Up until this point the religious beliefs of the tribes of south-east Arabia had primarily involved the worship of idols, although churches, such as those discovered at Sir Bani Yas in Abu Dhabi, attest to Christianity’s presence in the UAE at this time. According to Islamic accounts, Amr ibn al-As, one of the most trusted envoys of the Prophet Muhammad and the future conqueror of Egypt, was met by Christian bishops and monks when he was dispatched to the kings of Oman, and a dialogue ensued between them. They discussed the principles of Islam and the morals of the Prophet, after which the bishops and monks converted to Islam. A similar discussion is said to have taken place between al-As and the Al Julanda kings, to whom he presented a letter from the Prophet, calling on the people of Oman to convert to Islam. This they did peacefully, according to Ibn Sa’d, writer of the Kitab aṭ-Tabaqat al-Kabir, a biographical compendium of the important political and religious figures of early Islam.

Tradition has it that al-As met Abd first and then Jayfar, who had been in the Hajar Mountains at the time of the envoy’s arrival. The two brothers then called a meeting of all the Omani tribal leaders, who unanimously agreed to accept Islam. Further envoys were then despatched to the various regions of the peninsula, including Dibba, with all accepting the teachings of Islam. All, that is, except the Sasanians, who rejected all approaches and retained control of much of the coastline. As a consequence, the conversion of the Azd to Islam became enmeshed with their existing hostility towards the Sasanians.

Islam spelt the end of the Sasanian Empire. Immediately after their conversion, the Azd, boosted by Muslim forces from Medina, attacked the Sasanians and drove them from the peninsula, including from Kush in Ras Al Khaimah, which would soon transition into Julfar. According to the Annals of Oman by Sirhan Ibn Sa’id (a late nineteenth century English translation of part of the Kashf alghummah), the Azd and their commanders killed Maskan, the Sasanian administrator of Oman, captured their gold and silver, and granted them quarter provided they leave the country. This they did, leaving a chain of fortified settlements along the Batinah coast.

Map showing the extent of the Sasanian Empire across present-day Middle East and West Asia.

Following the defeat of the Sasanians, al-As remained in Oman until the death of the Prophet in AD 632 and the succession of Abu Bakr as the first of the Rashidun Caliphs. Almost immediately, the Ridda Wars broke out against Islamic rule in much of the Arabian peninsula. Alternatively known as the Wars of Apostasy, many tribes believed their ties with Medina came to an end with the death of the Prophet and openly rebelled. In south-east Arabia, that rebellion was centred on the east coast of the UAE, where forces loyal to a leader named Laqit bin Malik Al-Azdi fought against the combined forces of Medina and the Al Julanda. Although the ninth century scholar and historian Al-Tabari says that Al-Azdi achieved early success, the conflict culminated in the Battle of Dibba and a comprehensive victory for the followers of Islam.

From then on, the port of Julfar begins to play a prominent role in the political, social and mercantile affairs of the region. In AD 637, it is used as a staging post for the Islamic conquest of Iran and the defeat of the Sasanian Empire. Among those boarding the invasion fleet were men from the Azd and Abd al-Qays tribes. For both the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, Julfar would be of significant strategic importance throughout the ensuing centuries, although the tribes of south-east Arabia would remain a thorn in their sides for centuries.

ISLAMIC DYNASTIES IN THE ARAB WORLD

Despite their conversion to Islam and the defeat of the Sasanian Empire, the submission of tribal leaders to both the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates was never assured. If anything, the relationship between the tribes of south-east Arabia and the centralised authority of Damascus or Baghdad was defined by independence, hostility and open conflict. Within that environment, the port of Julfar became a pivotal rallying point for a series of bloody confrontations during the early years of Islam.

Our knowledge of what took place during the initial years of the Umayyad Caliphate is largely dependent on a handful of sources, including those of Sirhan Ibn Sa’id and Hamid ibn Muhammad ibn Ruzayq, the author of A History of the Imams and Seyyids of Oman. Other Abbasid-era historians, including Khalifah Ibn Khayyat, mention the campaigns against the sons of Abd bin Al Julanda – Suleiman and Said – only in passing and, as such, a clear picture of what took place has to be painstakingly pieced together.

What is clear is that the authority of the Umayyad caliphs in south-east Arabia appears to have been nominal at best until the accession of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan in AD 685. At first, envoys from the fifth Umayyad caliph were sent to the two rulers of Oman – Suleiman and Said. When these failed, a series of expeditions were despatched, the first of which was launched by Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the powerful governor of Iraq. Al-Hajjaj sent two separate forces – one by land and the other by sea – under the generalship of Qasim bin Sha’wah al-Muzani. Although the date is unknown, the naval force landed at Julfar, which then served as al-Muzani’s base for the duration of the campaign. In the ensuing confrontation, the Umayyad forces were defeated and al-Muzani killed.

On hearing of the defeat, Al-Hajjaj sent another army, this time 40,000 strong, according to Sa’id and Ruzayq. Under the leadership of al-Muzani’s brother, Muja’ah, two different land and sea forces were once again sent against the Azd. The former was defeated by Suleiman somewhere near Julfar, while the latter landed at a place called el-Yunaniyyah, which Ruzayq identifies as also being near Julfar, or at least within the boundaries of modern-day Ras Al Khaimah.

Faced with superior Umayyad forces, Said and his army retreated into the mountains while the Umayyad fleet sailed to Muscat, where Suleiman destroyed more than fifty of the caliphate’s ships. Another battle ensued and Muja’ah’s forces were once again defeated, leading to their retreat to Julfar and the summoning of reinforcements from Al-Hajjaj in Iraq. In response, Al-Hajjaj sent 5,000 Bedouin cavalry from Badiyat al-Sham under the command of Abd al-Rahman bin Suleiman. Realising they could no longer resist, Suleiman and Said, their families, and anyone else who wished to follow them, escaped by ship to Zanj on the east coast of Africa.

Archaeological evidence for this period is scarce, although the early centuries of Islamic rule are relatively well presented at Kush and on the island of Hulaylah. The former has been identified as the commercial centre of the original port of Julfar, with excavations revealing a substantial tower that dates from the early Islamic period. That tower would have been surrounded by a moat and guarded the harbour as part of the town’s defence system. An extensive but short-lived settlement is also known to have existed at the southern tip of the island of Hulaylah and there is evidence of early Islamic-era occupation at Khatt. At Hulaylah, knowledge of the settlement is based purely on ceramic evidence, which includes honeycomb ware and stamped white ware, both of which date to the late Sasanian and early Islamic period.

As is to be expected given its strategic location close the Strait of Hormuz, its safe harbour and access to the fertile palm gardens of Shimal, Julfar is the only settlement on the southern shores of the Arabian Gulf that is consistently mentioned by early Arab historians. Even the medieval geographer Al-Maqdisi knew very little of the wider region, despite it being central to successive military campaigns, including those orchestrated by the Abbasid caliphs during the ninth century.

An illustration depicting life during the Abbasid Period. The Arabic text is a prayer asking God for mercy, protection and blessings. © Alamy.

The early years of Abbasid rule were to be even bloodier than those of the Umayyads. In the final years of the Umayyad Caliphate, an independence movement re-emerged under the leadership of Al Julanda bin Masud, the first Ibadi imam of Oman and the grandson of Jayfar bin Al Julanda. When the Abbasids seized power in AD 750, the first Abbasid caliph, As-Saffah, sent an army led by Khazim ibn Khuzayma al-Tamimi to ensure the allegiance of the Azd. The Abbasid fleet sailed from Basra to the island of Kish and then on to Julfar, where it was met by the forces of Al Julanda. Al-Tamimi called for their loyalty to As-Saffah, but they refused, and a battle commenced. According to alTabari, the Abbasid forces set fire to the houses of Julfar, causing Al Julanda’s men to leave their positions and to rush to their families’ defence. In the ensuing chaos, Al Julanda and all of his followers were killed.

Al-Tabari’s account of the burning of Julfar gives us the first written evidence of the existence of arish-style housing. Common throughout Ras Al Khaimah and the wider UAE until the mid to latetwentieth century, arish houses were built using wooden frames made of mangrove poles or the split trunks of a palm tree. The fronds of the palm tree were then stripped and weaved together to create the walls, while full fronds were used to produce a thatch-like roof. Examples of such housing – dating back as far as the late Bronze Age – have been found at Shimal and the island of Hulaylah was probably settled with such buildings. Thanks to al-Tabari and excavations at Kush, we now know that at least part of the urban landscape of early Julfar was dominated by arish structures during the Abbasid period, although much of that housing would have lain within the palm gardens.

Julfar was once again used as a base for operations against the tribes of south-east Arabia in AD 892, when an expedition was sent against an Azd alliance by the Caliph Al-Mu’tadid. Led by Muhammad ibn Nur, the governor of Bahrain, the invading force was 25,000-strong and advanced, as always, by land and sea towards the foot of the Hajar Mountains. Julfar was seized after a short battle with its defenders and, with a naval base established, Nur advanced on Nizwa in modern day Oman. Despite stubborn resistance and a brief but ultimately unsuccessful counter offensive, much of the peninsula was devastated. According to Ruzayq, Nur ravaged the countryside, destroyed much of the region’s agricultural assets, demolished its falaj systems, tortured its nobles, and burnt its books.

As with the Umayyad period, very little archaeological evidence exists from the Abbasid era. Kush remains the most important site, although the original tower appears to have been abandoned in the early Islamic period and re-occupied at some stage during the ninth and tenth centuries. A handful of significant finds from this era, including two Dusun pottery fragments from China, indicate the existence of sea trade with the Far East, while archaeological surveys at Wadi Haqil have identified two farms dating from the same period. At Hulaylah, excavations point to peak settlement between the ninth and eleventh centuries, while Samarra horizon pottery dating from ninth-century Iraq has been discovered at Khatt. The same pottery has also been found at Wadi Safarfir, where a flourishing copper mining industry existed during the early Islamic era.

It is not until the later Islamic period that a wealth of archaeological evidence begins to broaden our understanding of life in Ras Al Khaimah. Combined with an upsurge in historical sources and the emergence of buildings such as the Queen of Sheba’s Palace, a far more prosperous and urbanised world begins to materialise. Nowhere exemplifies this better than Julfar, which was to become the most famed and prosperous trading town in the lower Gulf.

THE BEGINNINGS OF JULFAR

No other name evokes the spirit of Arabian adventure like Julfar. Romanticised and exoticised for more than a thousand years, it was the birthplace of the legendary navigator Ahmed ibn Majid, a focal point for maritime power, and the only port providing access from the Arabian Gulf to southeast Arabia. Its strategic location close to the Strait of Hormuz, its relationship with maritime trade, and the importance placed in it by successive empires meant that Julfar grew in both size and importance.

And yet its exact location remained a mystery until the middle of the twentieth century. Even though Beatrice de Cardi identified the site of medieval Julfar in 1968, subsequent excavations revealed that settlement of the site had begun sometime in the thirteenth century and terminated at some point during the sixteenth century. So where was the Julfar of the early Arab historians? Where was the Julfar of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates?

Archaeological digs at Julfar

What became clear with the discovery of Kush was that the port town had moved around the coastal plain as lagoons began to silt up and offshore sandbars began to emerge, making navigation impossible. All evidence of pre-Islamic and early Islamic Julfar therefore points to a single site – Kush. The archaeological tell has provided evidence of an early large, public building complex as well as a substantial tower and housing complexes that date until the end of the thirteenth century. It would have served not only as the administrative and commercial centre of the port, but also of the town’s agricultural hinterland and the housing that lay within it. That hinterland would have included palm gardens that formed a lush, fertile arc that ran from the foot of the Hajar Mountains towards Nakheel and Falayah. That fertile arc, fed by water from Wadi Bih, had been at the heart of life since the Hafit period.

The town itself would have included only a few buildings and nothing more, with the majority of the population living within the palm gardens, either in mud brick, stone or arish houses. Those gardens were the source of life for Julfar, providing a harvest of dates and other fruit such as oranges and lemons, as well as vegetables and fodder for livestock. Although the size of the population can only be guessed at, it would have been substantial, with early Julfar linked to the coast by a lagoon and a network of navigable channels, despite now lying a few kilometres inland. It was this lagoon, protected by an offshore sandbar, that provided a safe harbour and enabled the port to flourish.

Muslim historians have not presented a clear and accurate picture of the sequence of events relating to Julfar in the early Islamic period, but a number of geographers considered it to be one of the most significant towns in south-east Arabia. The late Abbasid-era geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi described Julfar as producing sheep, cheese and ghee in great quantity, much of which was exported to neighbouring territories. It also traded in pepper and possibly coffee, with the world’s oldest coffee bean (dating from the twelfth century) discovered at Kush in the late 1990s. The geographer and cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi also referred to Julfar as a long-established pearling centre, with the town connected by coastal trade routes to Bahrain – another pearling centre and one of the most economically prosperous ports in the Gulf.

From the Abbasid period onwards Julfar became an integral part of the Indian Ocean trade routes that connected the Arabian peninsula with Southeast Asia, India and East Africa. It is entirely plausible that these routes were already known to the inhabitants of Julfar, who provided the ships (possibly an early form of dhow), the expertise and the captains necessary for such trade. Certainly from the Abbasid period onwards, contact with China accelerated, hence the discovery of two Dusun pottery fragments at Kush.

However, towards the end of the thirteenth century, Kush appears to have been completely abandoned. This was probably due to the silting up of the lagoon, which would have disconnected the town from the coast and forced the port’s relocation to Mataf and Nudud. Writing in the twelfth century, Al-Idrisi describes boats having to unpack from a sandbank prior to reaching Julfar, indicating that from as early as the eleventh century, the edges of the lagoon were beginning to recede from Kush, heralding its end.

The former inhabitants of Kush headed towards the coast and to two sites known as Mataf and Nudud. Straddling a narrow creek that opened up into an extensive lagoon, they began as modest settlements dominated by arish housing. What would emerge, however, would be far greater and far more magnificent than anything that ever existed at Kush. Medieval travellers talk of a large, prosperous port town that dealt in amber and pearls, perfumes and incense, horses and dyes, and grew rich on the back of international trade. It became a starting point for pilgrimage to Mecca, a source of great wealth for the Kingdom of Hormuz (which Julfar was part of throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries) and was one of the most important and most magical harbours of its time.

When the Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa visited Julfar in the early years of the sixteenth century, he discovered a town occupied by “persons of worth, great navigators and wholesale dealers”. It was the birthplace of the great seafarer Ahmad Ibn Majid, whose body of navigational literature included the Kitab al-fawa’id fi usul ‘ilm al-bahr wa-al-qawa’id(Book of Useful Information on the Principles and Rules of Navigation), and although both old and new Julfar may have co-existed for a short period of time, the latter rapidly eclipsed the former.

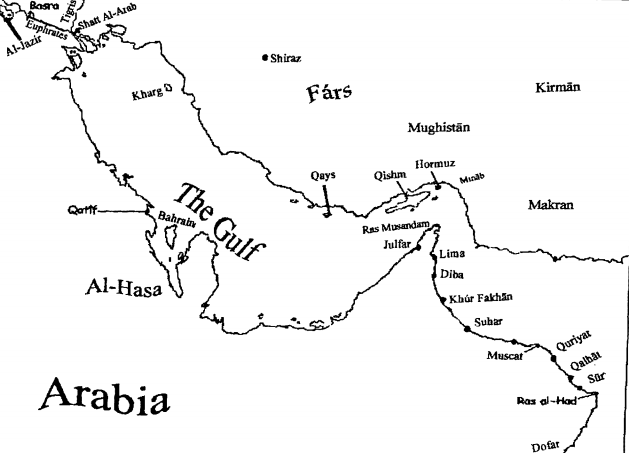

The Arabian Gulf and Coast in the sixteenth century.

Of all the historical figures associated with the wonder that was medieval Julfar, it is Ibn Majid who stands head and shoulders above them all. Now considered a national hero and a cultural icon, most of what we know about him stems from his corpus of literary works or from later references. He was a hugely experienced navigator, cartographer and poet and one of the great pioneers of navigational science, transforming Arab navigation in the Indian Ocean into a highly organised discipline. He also epitomised the continuation of a seafaring tradition that stretched back into the mists of time. Born into an active seagoing community during the first half of the fifteenth century, he was descended from a family that was rich in nautical history and was guided by the stories of the elderly sons of Julfar. He built upon the work of his grandfather and father, both of whom had navigated the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean and added to their knowledge with his own experience and learning. He drew upon religion, jurisprudence, arithmetic and astronomy, combining theoretical science with technical invention, and was the first to write down the art of navigation and to teach it in classical Arabic.

The meteoric rise of medieval Julfar was closely linked to the Kingdom of Hormuz, which relied on the town and its lush palm gardens not only for its agricultural needs, but for its troops and much of its wealth. A sizeable amount of Hormuz’s income came from tribute exacted from the ports that lay within its sphere of influence, chief among which was Julfar, where a local market economy, shipping, pearling, craftsmanship, pilgrimage and the trade in horses had ensured its rise to prominence. The Portuguese historian João de Barros, writing in 1553, noted that revenue collected for Hormuz from Julfar far exceeded anything paid by other towns along the coast of Oman, including Muscat, Dibba and Khor Fakkan.

Julfar’s wealth came from a variety of sources, but it was pearls that were arguably its greatest asset. In 1580, the Venetian jeweller and merchant Gasparo Balbi wrote that the best pearls in the world were to be found in Julfar, while the Portuguese explorer Pedro Teixeira talked of a fleet of fifty boats setting sail for the pearl banks every year. The Portuguese explorer Antonio Tenreiro also referred to ‘aljofre’, a smaller variety of pearl derived from the name Julfar, in 1528, and the port would remain a leading pearling centre in the Lower Gulf until the early years of the nineteenth century.

Such wealth enabled the inhabitants of Julfar to purchase manufactured goods such as textiles, metalwork and pottery, as well as luxury items like silk and porcelain. Archaeological discoveries at Mataf and Nudud provide ample evidence of this, including sizeable quantities of Chinese blue and white porcelain, Vietnamese brown painted stoneware, Southeast Asian green glazed stoneware, Indian glass bangles and Iranian pottery.

This wealth also led to the construction of grander and more imposing properties, including the Queen of Sheba’s Palace, which is situated on a rocky spur overlooking Shimal. Built for the ruler of Julfar, it is the only ancient Islamic palace known to exist in the UAE and combines defensive, domestic and representative architectural traditions of the middle Islamic period. Although only its foundations remain, it included cisterns, round towers, and a main entrance that was built into the centre of the southern wall. It is one of the first examples of the increasing stratification of society, with a ruling class buoyed by wealth beginning to stand out from the rest of society.

What flourished on the sites of Mataf and Nudud was an outstanding urban centre. There was a souk, a fort, a large mosque, a town wall, and a number of courtyard homes, as well as a dense network of stone and mud-brick houses and streets. The palm gardens adjacent to the old site of Kush increased their agricultural production, while a large-scale Julfar ware pottery industry began to emerge in the fourteenth century. In total, more than 40,000 people would have lived in northern Ras Al Khaimah during Julfar’s heyday, the majority of whom would have been protected by a large town wall now known as Wadi Sur, which ran in a straight line from the site of Sheba’s Palace to the creek of modern Ras Al Khaimah.

The remains of the Queen of Sheba’s Palace in the Hajar Mountains of Ras Al Khaimah.

Although the exact date of Wadi Sur’s construction is unknown, it was seven kilometres long, about five to six metres high, and included a series of semi-circular towers that were located every 150 metres. To the front would have been a large ditch that was dug into the gravel fan of Wadi Bih, behind which would have stood a rampart. On top of that would have been a mud brick wall at least two metres high, with walkways inside for troops to patrol. Triple the size of an average medieval town wall in Europe, it would have been manned by professional soldiers, including an elite force of trained archers, and protected the town from landward attacks by marauding Bedouin from the interior. Those Bedouin would have included the Banu Jabr, who had risen to power in eastern Arabia during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

As a monument to Julfar’s strength and wealth, Wadi Sur was unrivalled. It was one of the largest fortifications in south-east Arabia and yet by the end of the sixteenth century it was all but obsolete. The Portuguese replaced the Kingdom of Hormuz as the dominant power in the Arabian Gulf in the early sixteenth century, taking the island of Hormuz itself in 1507 and establishing a chain of fortified settlements across the Indian Ocean.

Although Julfar would only fall under direct Portuguese control for a short period of time, the location of the port began to shift for a third and final time. From the late fifteenth century onwards the population of Julfar had begun to shrink, leading to its abandonment by the mid-sixteenth century and the establishment of the new port of Ras Al Khaimah. The reasons for this move are probably similar to those that led to the relocation from Kush, with the lagoon behind Mataf and Nudud silting up. By the time the Qawasim began to appear as a naval power in the eighteenth century, the name of Ras Al Khaimah appears to have replaced that of Julfar almost completely. However, the ancient city of Julfar would remain embedded in the region’s imagination until the present day.

REFERENCES

Al-Rawas, ‘Ism ‘Ali Ahmed: Early Islamic Oman: A Political History (1990). Read More

Carter, Robert; Zhao, Bing; Lane, Kevin; Velde, Christian: The Rise and Ruin of a Medieval Port Town:

A Reconsideration of the Development of Julfar (2020). Read More

Kennet, Derek: Jazirat al-Hulayla – Early Julfar (1994). Read More

King, Geoffrey R: The Coming of Islam and the Islamic Period in the UAE (2001). Read More

Morley, Mike; Carter, Robert; Velde, Christian: Geoarchaeological Investigations at the Site of Julfar (al-Nudūd and al-MaΓāf), Ras al-Khaymah, UAE: Preliminary Results from the Auger-hole Survey (2011). Read More

Power, Timothy: Julfar and the Ports of Northern Oman (2012). Read More

Ruzayq, Hamid ibn Muhammad ibn: A History of the Imams and Seyyids of Oman (1871). Read More

Sa’id, Sirhan Ibn: Annals of Oman (1874). Read More

Velde, Christian; Hilal, Ahmed; Moellering, Imke: Wadi Sur in Ra’s al-Khaimah, One of the Largest Fortifications in South-eastern Arabia (2008). Read More

Velde, Christian: A Geographical History of Julfar (2012). Read More