| THE BEGINNINGS OF THE UAE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The British Protectorate and the Trucial States | Ras Al Khaimah and the Union | |||

As the British strengthened their foothold in Arabia, they established a Political Residency in the Gulf, with the main aim of safeguarding Britain’s imperial interests and the land and sea routes to India. At the time, the Qawasim had become successful merchants and the most powerful local tribe, challenging Oman’s maritime dominance. Britain had allied with the Omanis to ward off any potential French attacks and led to a conflict of interest with the Qawasim, who viewed the Brits with suspicion. Furthermore, Britain’s ambition to control the trade routes exacerbated the relationship between the two powers.

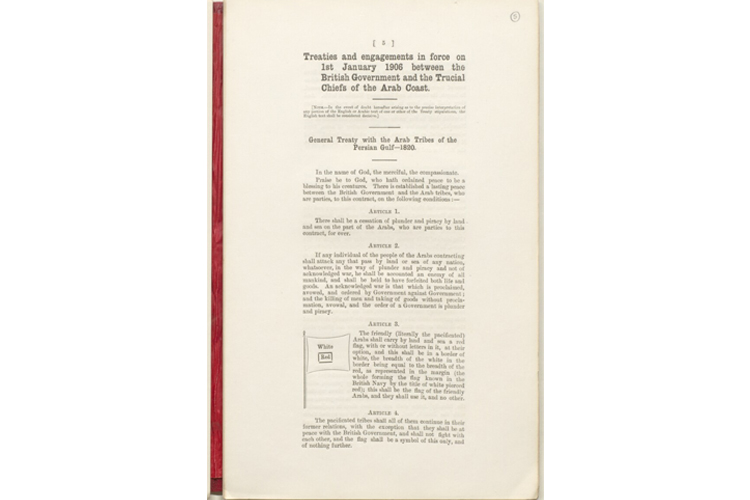

In 1806, the British signed an agreement with the Qawasim, in which both parties agreed they would respect each other’s property for peace to prevail; this accord marked the beginning of formal relations with the British in this region. However, the Gulf was far from peaceful, with frequent attacks on each other’s ships, which increased over time. To retaliate, the British embarked on a naval campaign in 1809 against the Qawasims. Hostilities between the two powers continued for another ten years, and finally in 1819, the British launched a naval expedition that razed Ras Al Khaimah to the ground. With no one left to challenge their dominion of the Gulf waters, the British imposed the General Maritime Treaty of 1820 on the rulers of the coastal emirates. Signed at the historic Falayah Fort in Ras Al Khaimah, the treaty gave the British forces a blanket right to monitor and govern the seas of the Arabian Gulf. This truce agreement also laid the foundation of the British protectorate in the region that lasted until December 1971, and the area gained the moniker, Trucial States.

The General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Arabian Gulf, 1820. © Qatar National Library

The same month, the British created the post of Political Agent for the Lower Gulf, whose job it was to ensure the enforcement of the treaty. Originally based on the island of Qeshm, along with a detachment of British troops, the agent remained there until 1822, when the position was replaced by a system of ‘maritime control’. That system involved the creation of a Persian Gulf Squadron that would continually police the coastline. Overall responsibility for the area also shifted to Bushehr, where the first British Resident for the Persian Gulf, Lieutenant John MacLeod, was stationed. In January 1823, MacLeod undertook a tour of the coast, visiting the principal sheikhs and beginning a tradition of yearly tours that would last well into the twentieth century.

By the time of MacLeod’s visit, Sheikh Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi had become the leader of all the Qawasim ports, with most sheikhs along the coast acknowledging his supremacy. In a letter to Francis Warden, chief secretary to the government in Bombay, MacLeod wrote that Al Qasimi was “the most prominent character in the Gulf” and that “Rasool Khyma is entirely subject to Sooltan bin Suggur, whose brother Sheikh Mohamed has been placed by him in charge of the Government”. MacLeod also noted that the “new town [of Ras Al Khaimah] consists of a great many huts built of reeds, with only one or two houses of mud. The creek still acts as a harbour for their boats”.

That harbour, wrote MacLeod, contained “a great many very fine vessels, probably at least thirty, capable of containing from fifty to one hundred men; he [Sheikh Sultan] is building a large buggalow [trading vessel] of about 120 tons, for the purpose it is said of trading to India. The other chiefs have very few boats, beyond those employed for fishing, probably none of them has more than three or four”. Sheikh Sultan himself was described as a “turbulent and ambitious man”, although greater in ability than the other rulers, and was “recognised as the superior of all the tribes on the coast from Rams to Sharga, excepting at Ejman”. MacLeod also added that, although Sheikh Sultan had very little direct authority over the other leaders, and the rulers of each state were elected by their own tribe, “Sooltan bin Suggur seems to have some power in influencing their choice, although he cannot impose a Shaikh upon them against their will: they seem in fact to be independent in respect to their own tribe, but acknowledge a general allegiance to Sooltan as the head of a superior tribe”.

Following his visit, MacLeod proposed the establishment of a Native Agency in Sharjah, whose job would be to cultivate good relations with the rulers, monitor activity along the Trucial Coast, and to help with the enforcement of the General Peace Treaty. As the years progressed and the number of treaties increased, this role would grow in importance, with the majority of agents either Arabicspeaking Muslims from the Persian coast or from the Indian subcontinent. “Our great object I think is to keep down hostilities at sea if possible,” wrote MacLeod to Warden, “and to prevent their quarrels amongst themselves from leading to a renewal of disorder; at the same time we must not interfere too far, and must observe great caution to avoid giving offence: much may be done by persevering in the system of steady control, combined with friendly intercourse, which Government has adopted.”

Although ships patrolled the Arabian Gulf in an effort to eradicate piracy, Britain was not involved in the internal politics of each state, nor did the General Peace Treaty of 1820 “limit the right of the Chiefs to carry on acknowledged war with each other by sea”, wrote Charles Aitchison, undersecretary to the government of India. In his A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries, which was first published in 1862, Aitchison noted that attacks by tribal leaders on one another continued to occur. These would persist well into the twentieth century and would be a constant source of acrimony. Tribal disputes, feuds, shifting allegiances, and even open warfare flourished, much as they had done for centuries.

In December 1831, for example, Sheikh Sultan and “his dependent (the Chief of Ejman) declared war against the Beniyas [Bani Yas]”, wrote Lieutenant Arnold Burrowes Kemball, Assistant Resident for the Persian Gulf. In 1833, the Qawasim blockaded the Bani Yas port of Abu Dhabi, with hostilities not brought to an end until 1834. Conflicts with Oman also continued, as did hostilities between other tribes along the coast and with the Bedouin of the interior. The latter were of such concern that Sheikh Sultan requested permission from MacLeod to build defensive fortifications along the landward side of Ras Al Khaimah. These would enable the town to protect itself from the Bedouin, who “took advantage of the defenceless state of the place, to come down and attack it during the pearl fishing season, when all the men were at sea”.

Although the British were initially unwilling or unable to prevent all conflict at sea, in 1835 the Assistant Resident for the Persian Gulf, Captain Samuel Hennell, proposed a truce forbidding maritime attacks during the forthcoming pearling season. Signed by the rulers of Sharjah, Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Ajman, the truce committed them to peace for a period of six months. Guaranteed by the British Resident and enforced by the navy’s cruisers, the peace held, and further treaties were signed in 1836 and 1837. The following year, the length of the truce was extended to twelve months on the suggestion of Al Qasimi, according Kemball, who wrote of the truces in his Observations on the Past Policy of the British Government Towards the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf.

“In 1838, on the Resident’s making a tour of the Arabian Coast, Shaikh Sultan bin Suggur not only expressed his earnest desire for a renewal of the truce, but added that it would afford him sincere pleasure if it could be changed into the establishment of a permanent peace upon the seas,” wrote Kemball. “On certain objections being adduced to this proposition, he urged the extension of the truce, and suspension of hostilities, for twelve instead of eight months, and Shaikh Khaleefa and the other parties consenting to this arrangement, the truce was drawn out accordingly, and duly signed by each. It was again renewed for the same period in the years 1839, 1840, 1841, and 1842 successively, without the slightest demur or objection.”

A ten-year truce was eventually signed on 1 June 1843. This, in turn, led to the Perpetual Maritime Truce of 1853, which was signed on 4 May of that year. Sheikh Sultan signed as the “Chief of the Joasmees”, with the treaty committing the signatories, as well as their heirs and successors, to “conclude together a lasting and inviolable peace from this time forth in perpetuity”. Consisting of three articles, the truce stated that “there shall be a complete cessation of hostilities at sea between our respective subjects and dependents, and a perfect maritime truce shall endure between ourselves and between our successors, respectively, for evermore.”

From that moment on the area previously referred to as the ‘Pirate Coast’ would become theTrucial Coast, and the tribal confederations that lived along it, the Trucial States. (It would also be referred to as Trucial Oman). The signing of the Perpetual Maritime Truce saw all of the Trucial States’ rulers agree that any disputes or acts of aggression should be escalated to the “British Resident or the Commodore at Bassidore [Basaidu in Iran]”, who would then “forthwith take the necessary steps for obtaining reparation for the injury inflicted, provided that its occurrence can be satisfactorily proved”. Further treaties were also entered into throughout the course of the nineteenth century, most notably an anti-slavery agreement that was signed on 10 December 1847. The treaty meant that the Qawasim and all other signatories agreed to “prohibit the exportation of slaves from the coasts of Africa and elsewhere on board of my vessels and those belonging to my subjects or dependents”. Instigated by Hennell, who by the time of the signing of the treaty had become the British Resident for the Persian Gulf, the agreement was followed by further commitments to the abolition of slavery.

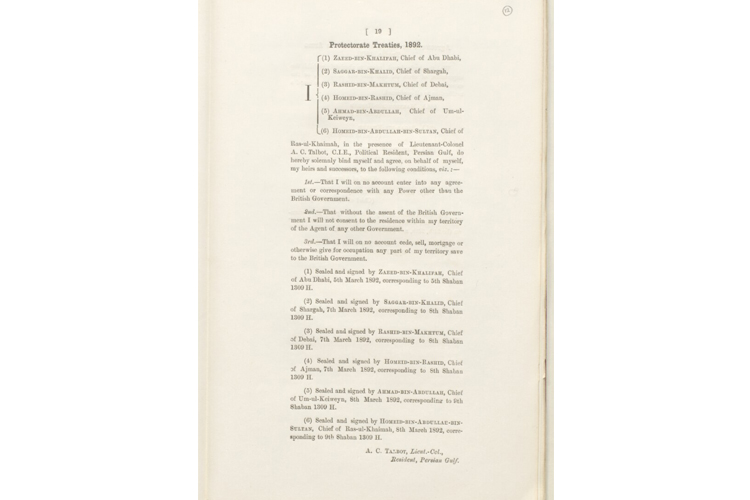

It wasn’t until the signing of an Exclusive Agreement in 1892, however, that the foreign affairs of Ras Al Khaimah and the other states finally fell under direct British control. A response to the increasing threat posed to British interests by French, Russian and Turkish overtures in the Arabian Gulf, the Exclusive Agreement ensured that each leader bound themselves, their heirs and their successors to “on no account enter into any agreement or correspondence with any power other than the British Government”. It also stipulated that each ruler would “on no account cede, sell, mortgage or otherwise give for occupation any part of my territory, save to the British Government”. In return, the British assumed responsibility for their defence and external relations. In doing so, the Trucial States became an informal British protectorate, and would remain so until all the treaties were revoked on 1 December 1971.

The General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Arabian Gulf, 1820. © Qatar National Library

The same month, the British created the post of Political Agent for the Lower Gulf, whose job it was to ensure the enforcement of the treaty. Originally based on the island of Qeshm, along with a detachment of British troops, the agent remained there until 1822, when the position was replaced by a system of ‘maritime control’. That system involved the creation of a Persian Gulf Squadron that would continually police the coastline. Overall responsibility for the area also shifted to Bushehr, where the first British Resident for the Persian Gulf, Lieutenant John MacLeod, was stationed. In January 1823, MacLeod undertook a tour of the coast, visiting the principal sheikhs and beginning a tradition of yearly tours that would last well into the twentieth century.

By the time of MacLeod’s visit, Sheikh Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi had become the leader of all the Qawasim ports, with most sheikhs along the coast acknowledging his supremacy. In a letter to Francis Warden, chief secretary to the government in Bombay, MacLeod wrote that Al Qasimi was “the most prominent character in the Gulf” and that “Rasool Khyma is entirely subject to Sooltan bin Suggur, whose brother Sheikh Mohamed has been placed by him in charge of the Government”. MacLeod also noted that the “new town [of Ras Al Khaimah] consists of a great many huts built of reeds, with only one or two houses of mud. The creek still acts as a harbour for their boats”.

That harbour, wrote MacLeod, contained “a great many very fine vessels, probably at least thirty, capable of containing from fifty to one hundred men; he [Sheikh Sultan] is building a large buggalow [trading vessel] of about 120 tons, for the purpose it is said of trading to India. The other chiefs have very few boats, beyond those employed for fishing, probably none of them has more than three or four”. Sheikh Sultan himself was described as a “turbulent and ambitious man”, although greater in ability than the other rulers, and was “recognised as the superior of all the tribes on the coast from Rams to Sharga, excepting at Ejman”. MacLeod also added that, although Sheikh Sultan had very little direct authority over the other leaders, and the rulers of each state were elected by their own tribe, “Sooltan bin Suggur seems to have some power in influencing their choice, although he cannot impose a Shaikh upon them against their will: they seem in fact to be independent in respect to their own tribe, but acknowledge a general allegiance to Sooltan as the head of a superior tribe”.

Following his visit, MacLeod proposed the establishment of a Native Agency in Sharjah, whose job would be to cultivate good relations with the rulers, monitor activity along the Trucial Coast, and to help with the enforcement of the General Peace Treaty. As the years progressed and the number of treaties increased, this role would grow in importance, with the majority of agents either Arabicspeaking Muslims from the Persian coast or from the Indian subcontinent. “Our great object I think is to keep down hostilities at sea if possible,” wrote MacLeod to Warden, “and to prevent their quarrels amongst themselves from leading to a renewal of disorder; at the same time we must not interfere too far, and must observe great caution to avoid giving offence: much may be done by persevering in the system of steady control, combined with friendly intercourse, which Government has adopted.”

Although ships patrolled the Arabian Gulf in an effort to eradicate piracy, Britain was not involved in the internal politics of each state, nor did the General Peace Treaty of 1820 “limit the right of the Chiefs to carry on acknowledged war with each other by sea”, wrote Charles Aitchison, undersecretary to the government of India. In his A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries, which was first published in 1862, Aitchison noted that attacks by tribal leaders on one another continued to occur. These would persist well into the twentieth century and would be a constant source of acrimony. Tribal disputes, feuds, shifting allegiances, and even open warfare flourished, much as they had done for centuries.

In December 1831, for example, Sheikh Sultan and “his dependent (the Chief of Ejman) declared war against the Beniyas [Bani Yas]”, wrote Lieutenant Arnold Burrowes Kemball, Assistant Resident for the Persian Gulf. In 1833, the Qawasim blockaded the Bani Yas port of Abu Dhabi, with hostilities not brought to an end until 1834. Conflicts with Oman also continued, as did hostilities between other tribes along the coast and with the Bedouin of the interior. The latter were of such concern that Sheikh Sultan requested permission from MacLeod to build defensive fortifications along the landward side of Ras Al Khaimah. These would enable the town to protect itself from the Bedouin, who “took advantage of the defenceless state of the place, to come down and attack it during the pearl fishing season, when all the men were at sea”.

Although the British were initially unwilling or unable to prevent all conflict at sea, in 1835 the Assistant Resident for the Persian Gulf, Captain Samuel Hennell, proposed a truce forbidding maritime attacks during the forthcoming pearling season. Signed by the rulers of Sharjah, Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Ajman, the truce committed them to peace for a period of six months. Guaranteed by the British Resident and enforced by the navy’s cruisers, the peace held, and further treaties were signed in 1836 and 1837. The following year, the length of the truce was extended to twelve months on the suggestion of Al Qasimi, according Kemball, who wrote of the truces in his Observations on the Past Policy of the British Government Towards the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf.

“In 1838, on the Resident’s making a tour of the Arabian Coast, Shaikh Sultan bin Suggur not only expressed his earnest desire for a renewal of the truce, but added that it would afford him sincere pleasure if it could be changed into the establishment of a permanent peace upon the seas,” wrote Kemball. “On certain objections being adduced to this proposition, he urged the extension of the truce, and suspension of hostilities, for twelve instead of eight months, and Shaikh Khaleefa and the other parties consenting to this arrangement, the truce was drawn out accordingly, and duly signed by each. It was again renewed for the same period in the years 1839, 1840, 1841, and 1842 successively, without the slightest demur or objection.”

A ten-year truce was eventually signed on 1 June 1843. This, in turn, led to the Perpetual Maritime Truce of 1853, which was signed on 4 May of that year. Sheikh Sultan signed as the “Chief of the Joasmees”, with the treaty committing the signatories, as well as their heirs and successors, to “conclude together a lasting and inviolable peace from this time forth in perpetuity”. Consisting of three articles, the truce stated that “there shall be a complete cessation of hostilities at sea between our respective subjects and dependents, and a perfect maritime truce shall endure between ourselves and between our successors, respectively, for evermore.”

From that moment on the area previously referred to as the ‘Pirate Coast’ would become theTrucial Coast, and the tribal confederations that lived along it, the Trucial States. (It would also be referred to as Trucial Oman). The signing of the Perpetual Maritime Truce saw all of the Trucial States’ rulers agree that any disputes or acts of aggression should be escalated to the “British Resident or the Commodore at Bassidore [Basaidu in Iran]”, who would then “forthwith take the necessary steps for obtaining reparation for the injury inflicted, provided that its occurrence can be satisfactorily proved”. Further treaties were also entered into throughout the course of the nineteenth century, most notably an anti-slavery agreement that was signed on 10 December 1847. The treaty meant that the Qawasim and all other signatories agreed to “prohibit the exportation of slaves from the coasts of Africa and elsewhere on board of my vessels and those belonging to my subjects or dependents”. Instigated by Hennell, who by the time of the signing of the treaty had become the British Resident for the Persian Gulf, the agreement was followed by further commitments to the abolition of slavery.

It wasn’t until the signing of an Exclusive Agreement in 1892, however, that the foreign affairs of Ras Al Khaimah and the other states finally fell under direct British control. A response to the increasing threat posed to British interests by French, Russian and Turkish overtures in the Arabian Gulf, the Exclusive Agreement ensured that each leader bound themselves, their heirs and their successors to “on no account enter into any agreement or correspondence with any power other than the British Government”. It also stipulated that each ruler would “on no account cede, sell, mortgage or otherwise give for occupation any part of my territory, save to the British Government”. In return, the British assumed responsibility for their defence and external relations. In doing so, the Trucial States became an informal British protectorate, and would remain so until all the treaties were revoked on 1 December 1971.

The Protectorate treaties from 1892, which made the Trucial States an informal British protectorate. © Qatar National Library

The Exclusive Agreement was signed on 8 March 1892 by Sheikh Humaid bin Abdullah Al Qasimi of Ras Al Khaimah and paved the way for years of relative stability. Although various conflicts would punctuate the latter years of the nineteenth century and even the early years of the twentieth century, Ras Al Khaimah enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity. The coastal towns attracted increasing migration from among the Bedouin of the interior, and its land and possessions increased. It was also a period of construction, with many of Ras Al Khaimah’s historic buildings built during this period. Khuzam Tower, the Square Tower of Mu’airidh, and the fort of Al Kosaidat were all constructed in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Up until the death of Sheikh Sultan, Ras Al Khaimah and Sharjah were, for the most part, ruled jointly, with only a few notable disruptions to the continuity of their leadership. Sheikh Sultan’s death in 1866, however, ushered in a period of uncertainty, with his son, Sheikh Khalid bin Sultan Al Qasimi, killed in battle less than two years into his reign. Sheikh Khalid’s death was followed by the reign of his brother, Sheikh Salim bin Sultan Al Qasimi, although his hold on Ras Al Khaimah would last only a year. In 1869, Ras Al Khaimah and its dependencies became a separate sheikhdom under Sheikh Humaid bin Abdullah Al Qasimi and would remain so until his death in 1900.

When Sheikh Humaid died, Qawasim rule was unified once again under Sheikh Saqr bin Khalid Al Qasimi, the ruler of Sharjah. Sheikh Saqr’s son, Khalid bin Saqr Al Qasimi, would act as governor of Ras Al Khaimah until his death in 1909, when Sheikh Salim bin Sultan Al Qasimi, a former ruler of Sharjah, was appointed governor. The previous, if brief, ruler of Ras Al Khaimah from 1868 to 1869, Sheikh Salim would consolidate power to the point where the emirate was effectively an independent entity. He took control of a town that boasted a little under 1,000 houses and a population of between 4,000 and 5,000. When Lorimer wrote his Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, he noted that the number of “genuine Qawasim” in the Trucial States (i.e. those directly related to the ruler) numbered only 18 adult males. Five lived in Sharjah, including the sheikh himself, eight in Ras Al Khaimah, two in Ajman and three in Hamriyah.

Compared with the early part of the nineteenth century, very few descriptions of Ras Al Khaimah exist for the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. British reports were mainly concerned with the political machinations of the various states and paid little attention to the people or towns of the Trucial States. Even Percy Cox, the Political Resident for the Persian Gulf between 1904 and 1919, provided only the briefest of descriptions in his travel journal, Some Excursions in Oman. He described the plain of Sir, which “runs for about seven miles south of Ras Al Khaimah and contains ten villages boasting some 2,500 inhabitants and gardens containing about 10,000 date trees”. A survey of Ras Al Khaimah was undertaken by Commander F. H. Walker aboard HMS Odin in 1910, which showed the entrance to the harbour being much further up the coast than it is today, but very little else exists outside of British administrative correspondence.

Almost a century of British involvement with the Trucial States would culminate in the first visit of a Viceroy and Governor-General of India to the Arabian Gulf in 1903. Lord Curzon’s arrival off the coast of Sharjah on 21 November was all pomp and pageantry, with the Viceroy addressing the assembled rulers and reaffirming Britain’s commitment to “guardianship and protection”. Declaring the British government as “overlords and protectors”, Curzon said that “the British Government have no desire to interfere, and have never interfered, in your internal affairs, provided that the Chiefs govern their territories with justice, and respect the rights of the foreign traders residing therein. If any internal disputes occur, you will always find a friend in the British Resident, who will use his influence, as he has frequently done in the past, to prevent these dissensions from coming to a head, and to maintain the status quo.”

Following the conclusion of Curzon’s visit, each sheikh was presented with a sword, a gold watch and chain, and a sporting rifle. A rifle was also given to each of the sheikhs’ sons.

After Sheikh Salim’s death in 1919, his son Muhammad briefly acted as governor until his brother, Sheikh Sultan bin Salim Al Qasimi, took over and, in 1921, achieved full independence for Ras Al Khaimah. Although the British Resident for the Persian Gulf, Arthur Prescott Trevor, initially believed Sheikh Sultan to be too young to take control of an independent Ras Al Khaimah, by the following year the government in Bombay had recognised him as ruler, which it did officially on 7 July 1921, making Ras Al Khaimah the sixth Trucial State and establishing its independence from Sharjah.

The Protectorate treaties from 1892, which made the Trucial States an informal British protectorate. © Qatar National Library

The Exclusive Agreement was signed on 8 March 1892 by Sheikh Humaid bin Abdullah Al Qasimi of Ras Al Khaimah and paved the way for years of relative stability. Although various conflicts would punctuate the latter years of the nineteenth century and even the early years of the twentieth century, Ras Al Khaimah enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity. The coastal towns attracted increasing migration from among the Bedouin of the interior, and its land and possessions increased. It was also a period of construction, with many of Ras Al Khaimah’s historic buildings built during this period. Khuzam Tower, the Square Tower of Mu’airidh, and the fort of Al Kosaidat were all constructed in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Up until the death of Sheikh Sultan, Ras Al Khaimah and Sharjah were, for the most part, ruled jointly, with only a few notable disruptions to the continuity of their leadership. Sheikh Sultan’s death in 1866, however, ushered in a period of uncertainty, with his son, Sheikh Khalid bin Sultan Al Qasimi, killed in battle less than two years into his reign. Sheikh Khalid’s death was followed by the reign of his brother, Sheikh Salim bin Sultan Al Qasimi, although his hold on Ras Al Khaimah would last only a year. In 1869, Ras Al Khaimah and its dependencies became a separate sheikhdom under Sheikh Humaid bin Abdullah Al Qasimi and would remain so until his death in 1900.

When Sheikh Humaid died, Qawasim rule was unified once again under Sheikh Saqr bin Khalid Al Qasimi, the ruler of Sharjah. Sheikh Saqr’s son, Khalid bin Saqr Al Qasimi, would act as governor of Ras Al Khaimah until his death in 1909, when Sheikh Salim bin Sultan Al Qasimi, a former ruler of Sharjah, was appointed governor. The previous, if brief, ruler of Ras Al Khaimah from 1868 to 1869, Sheikh Salim would consolidate power to the point where the emirate was effectively an independent entity. He took control of a town that boasted a little under 1,000 houses and a population of between 4,000 and 5,000. When Lorimer wrote his Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, he noted that the number of “genuine Qawasim” in the Trucial States (i.e. those directly related to the ruler) numbered only 18 adult males. Five lived in Sharjah, including the sheikh himself, eight in Ras Al Khaimah, two in Ajman and three in Hamriyah.

Compared with the early part of the nineteenth century, very few descriptions of Ras Al Khaimah exist for the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. British reports were mainly concerned with the political machinations of the various states and paid little attention to the people or towns of the Trucial States. Even Percy Cox, the Political Resident for the Persian Gulf between 1904 and 1919, provided only the briefest of descriptions in his travel journal, Some Excursions in Oman. He described the plain of Sir, which “runs for about seven miles south of Ras Al Khaimah and contains ten villages boasting some 2,500 inhabitants and gardens containing about 10,000 date trees”. A survey of Ras Al Khaimah was undertaken by Commander F. H. Walker aboard HMS Odin in 1910, which showed the entrance to the harbour being much further up the coast than it is today, but very little else exists outside of British administrative correspondence.

Almost a century of British involvement with the Trucial States would culminate in the first visit of a Viceroy and Governor-General of India to the Arabian Gulf in 1903. Lord Curzon’s arrival off the coast of Sharjah on 21 November was all pomp and pageantry, with the Viceroy addressing the assembled rulers and reaffirming Britain’s commitment to “guardianship and protection”. Declaring the British government as “overlords and protectors”, Curzon said that “the British Government have no desire to interfere, and have never interfered, in your internal affairs, provided that the Chiefs govern their territories with justice, and respect the rights of the foreign traders residing therein. If any internal disputes occur, you will always find a friend in the British Resident, who will use his influence, as he has frequently done in the past, to prevent these dissensions from coming to a head, and to maintain the status quo.”

Following the conclusion of Curzon’s visit, each sheikh was presented with a sword, a gold watch and chain, and a sporting rifle. A rifle was also given to each of the sheikhs’ sons.

After Sheikh Salim’s death in 1919, his son Muhammad briefly acted as governor until his brother, Sheikh Sultan bin Salim Al Qasimi, took over and, in 1921, achieved full independence for Ras Al Khaimah. Although the British Resident for the Persian Gulf, Arthur Prescott Trevor, initially believed Sheikh Sultan to be too young to take control of an independent Ras Al Khaimah, by the following year the government in Bombay had recognised him as ruler, which it did officially on 7 July 1921, making Ras Al Khaimah the sixth Trucial State and establishing its independence from Sharjah.

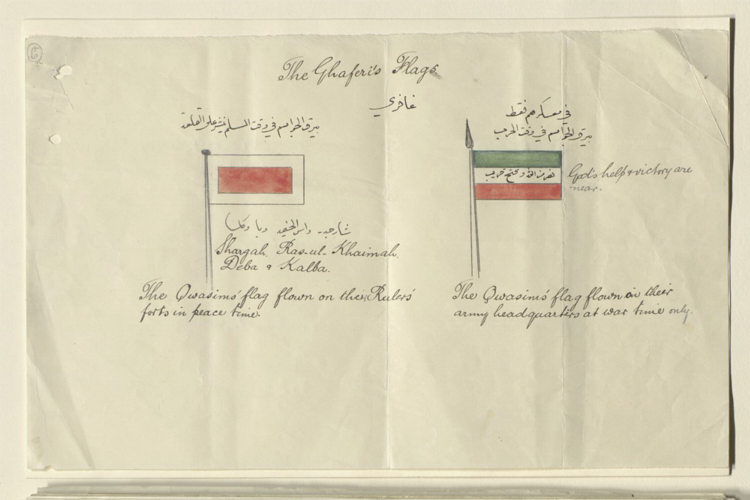

The Qawasim flags – both Sharjah and Ras Al Khaimah had the same flags since they are ruled by two branches of the same family. © Qatar National Library

The Qawasim flags – both Sharjah and Ras Al Khaimah had the same flags since they are ruled by two branches of the same family. © Qatar National Library

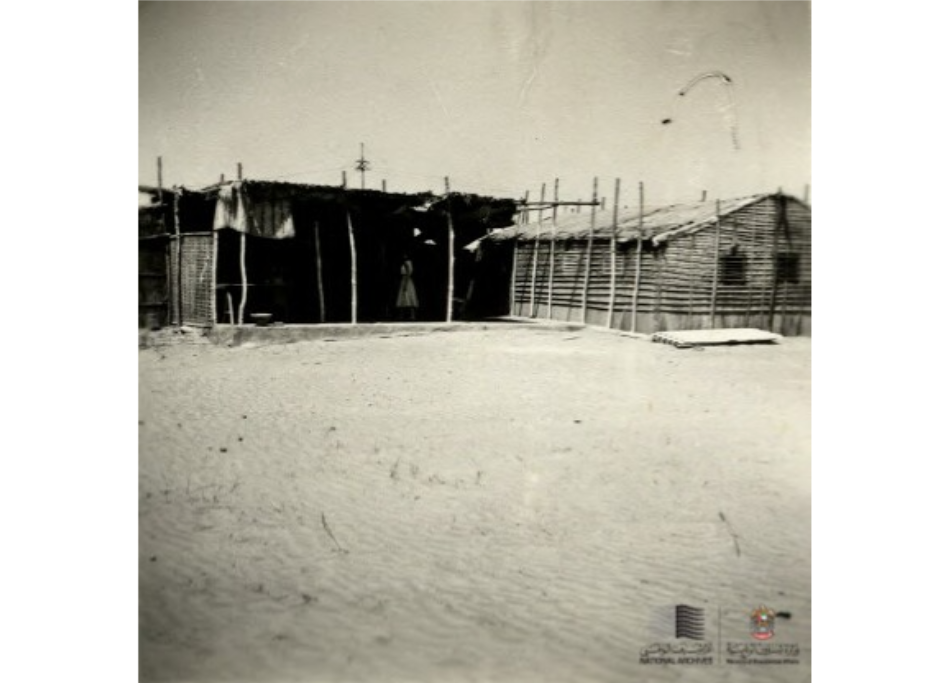

The experimental farm and school at Digdaga, which was established in 1955. © National Archives, UAE

Social and economic development of the Trucial States had been neglected by the British and was a significant bone of contention for Sheikh Saqr, who sought to invest in Ras Al Khaimah’s agricultural potential. The experimental farm and school at Digdaga had been established in 1955 and the emirate would benefit from increased investment throughout the 1960s. This not only applied to agriculture, but to the provision of water supplies, the building of power stations, the development of schools, and improvements to the town’s port. The construction of Ras Al Khaimah’s first town roads also began in 1967 under the supervision of Robert Webb, a civil engineer working for Sir William Halcrow & Partners, while the Trucial States Development Fund financed the construction of the Sharjah to Ras Al Khaimah highway. Completed in 1968, the road was part of a growing interstate network that also included the Dubai to Sharjah highway, with more than 220 kilometres of roads built between 1964 and 1971.

The creation of a modern interstate transportation network increased connectivity and brought the seven states closer together, both physically and psychologically. It was one of many initiatives that promoted common cause among the leaders during the existence of the Trucial States Council and paved the way for the emergence of the United Arab Emirates, the formation of which would come quicker than anybody anticipated.

The experimental farm and school at Digdaga, which was established in 1955. © National Archives, UAE

Social and economic development of the Trucial States had been neglected by the British and was a significant bone of contention for Sheikh Saqr, who sought to invest in Ras Al Khaimah’s agricultural potential. The experimental farm and school at Digdaga had been established in 1955 and the emirate would benefit from increased investment throughout the 1960s. This not only applied to agriculture, but to the provision of water supplies, the building of power stations, the development of schools, and improvements to the town’s port. The construction of Ras Al Khaimah’s first town roads also began in 1967 under the supervision of Robert Webb, a civil engineer working for Sir William Halcrow & Partners, while the Trucial States Development Fund financed the construction of the Sharjah to Ras Al Khaimah highway. Completed in 1968, the road was part of a growing interstate network that also included the Dubai to Sharjah highway, with more than 220 kilometres of roads built between 1964 and 1971.

The creation of a modern interstate transportation network increased connectivity and brought the seven states closer together, both physically and psychologically. It was one of many initiatives that promoted common cause among the leaders during the existence of the Trucial States Council and paved the way for the emergence of the United Arab Emirates, the formation of which would come quicker than anybody anticipated.

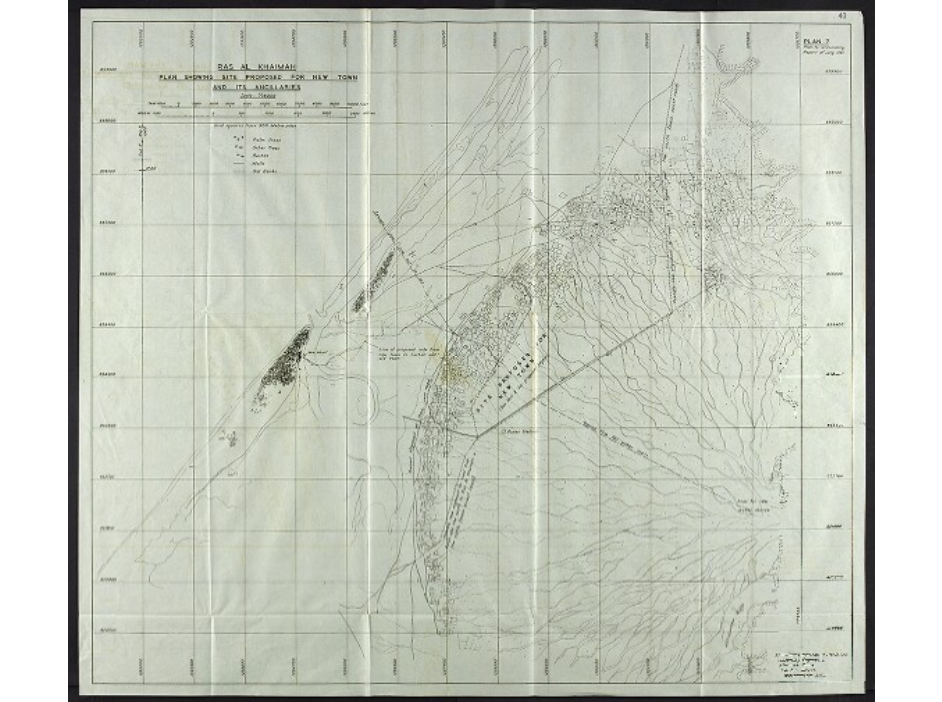

Plans for economic development and expansion of Ras Al Khaimah, 1961. © National Archives, UAE

Plans for economic development and expansion of Ras Al Khaimah, 1961. © National Archives, UAE

One of the numerous meetings held with the rulers of the Trucial States for the formation of a unified federation, 1969. © National Archives, UAE

The Union Accord was a remarkable document that lay the foundations for a wider federation. Within a week, the two leaders had invited the rulers of Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah, Umm Al Quwain, Ajman and Fujairah, as well as those of Bahrain and Qatar, to join negotiations for the formation of a union. Between 25 and 27 February 1968, all nine leaders met in Dubai for discussions, leading to the signing of an eleven-point agreement that would form the basis of the ‘Federation of the Arab Emirates’. The agreement stipulated that the purpose of the federation was, amongst other things, to cement ties between members in all fields and to coordinate plans for their development and prosperity.

At the time, Sheikh Saqr stated that the agreement was “a necessary step forward to ensure the future stability of all the emirates, and therefore the Gulf”, and he added. “I urge my fellow rulers, and everyone here, to continue this progress in order that we may soon stand together as a strong, viable federation which can take our people into the future.”

Bahrain and Qatar would eventually withdraw from the negotiations, leaving the leaders of the seven Trucial States to discuss the formation of a ‘Union of Arab Emirates’. On 10 July 1971, those rulers met in Dubai to hammer out any outstanding issues and move towards a final agreement. The leaders agreed to a union and announced the formation of the United Arab Emirates on 18 July 1971. “The Supreme Council felicitates the people of the United Arab Emirates, as well as the Arab people, and our friends around the world, and declares the United Arab Emirates as an independent sovereign state being a part of the Arab World,” was the meeting’s culminating declaration. When the British finally left on 30 November, bringing an end to more than 150 years of involvement in the affairs of the Trucial States, the foundation of an independent United Arab Emirates was formally proclaimed on 2 December 1971.

Alec Douglas-Home, the UK’s Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, announced the formation of the union in the House of Commons on 6 December 1971: “I am glad to tell the House that the United Arab Emirates was formally established last Thursday, 2nd December.” He also added that the Ruler of Abu Dhabi was sworn in as the President of the nascent country.

Speaking to the newly formed Supreme Council, Sheikh Saqur said, “As we are building a union in this part of our great Arab world … it would only be a brick in the edifice of the Arab nation that extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Gulf.”

Sheikh Saqr would stand by his words, ensuring that Ras Al Khaimah would be at the very heart of the UAE. In the following decades, the emirate would become an integral part of the union, providing the raw materials for the country’s development, leading the way in the creation of a diversified economy, and emerging as a world class tourism destination.

One of the numerous meetings held with the rulers of the Trucial States for the formation of a unified federation, 1969. © National Archives, UAE

The Union Accord was a remarkable document that lay the foundations for a wider federation. Within a week, the two leaders had invited the rulers of Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah, Umm Al Quwain, Ajman and Fujairah, as well as those of Bahrain and Qatar, to join negotiations for the formation of a union. Between 25 and 27 February 1968, all nine leaders met in Dubai for discussions, leading to the signing of an eleven-point agreement that would form the basis of the ‘Federation of the Arab Emirates’. The agreement stipulated that the purpose of the federation was, amongst other things, to cement ties between members in all fields and to coordinate plans for their development and prosperity.

At the time, Sheikh Saqr stated that the agreement was “a necessary step forward to ensure the future stability of all the emirates, and therefore the Gulf”, and he added. “I urge my fellow rulers, and everyone here, to continue this progress in order that we may soon stand together as a strong, viable federation which can take our people into the future.”

Bahrain and Qatar would eventually withdraw from the negotiations, leaving the leaders of the seven Trucial States to discuss the formation of a ‘Union of Arab Emirates’. On 10 July 1971, those rulers met in Dubai to hammer out any outstanding issues and move towards a final agreement. The leaders agreed to a union and announced the formation of the United Arab Emirates on 18 July 1971. “The Supreme Council felicitates the people of the United Arab Emirates, as well as the Arab people, and our friends around the world, and declares the United Arab Emirates as an independent sovereign state being a part of the Arab World,” was the meeting’s culminating declaration. When the British finally left on 30 November, bringing an end to more than 150 years of involvement in the affairs of the Trucial States, the foundation of an independent United Arab Emirates was formally proclaimed on 2 December 1971.

Alec Douglas-Home, the UK’s Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, announced the formation of the union in the House of Commons on 6 December 1971: “I am glad to tell the House that the United Arab Emirates was formally established last Thursday, 2nd December.” He also added that the Ruler of Abu Dhabi was sworn in as the President of the nascent country.

Speaking to the newly formed Supreme Council, Sheikh Saqur said, “As we are building a union in this part of our great Arab world … it would only be a brick in the edifice of the Arab nation that extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Gulf.”

Sheikh Saqr would stand by his words, ensuring that Ras Al Khaimah would be at the very heart of the UAE. In the following decades, the emirate would become an integral part of the union, providing the raw materials for the country’s development, leading the way in the creation of a diversified economy, and emerging as a world class tourism destination.

The Rulers of the Emirates celebrating the union of the seven emirates to form the United Arab Emirates. © National Archives, UAE

The Rulers of the Emirates celebrating the union of the seven emirates to form the United Arab Emirates. © National Archives, UAE